Doi.org/10.1038/nature21707

Target Article

Hughes et al. (2017). Global Warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature, 543, 373-377 Available at: https://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v543/n7645/full/nature21707.html doi:10.1038/nature21707

Significant Claim

Hughes et al. (2017)[1] has documented the mass coral bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) that occurred in 2016. This was the third major bleaching event since the 1990’s with other documented events occurring in 1998 and 2002. The bleaching event was attributed to global warming, and thus immediate global action to curb future warming is essential to secure the future of coral reefs. In this letter we will deliberately put aside the questions of the relationship between climate change and bleaching and focus on the methodology used in this research, which may well have misrepresented the level of bleaching. Bleaching occurs when coral polyps expel the symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) that reside inside the polyp. This sometimes occurs due to very high water temperatures. Because the zooxanthellae are responsible for much of the colour in corals, bleaching turns the coral white. In addition, the zooxanthellae provide a considerable fraction of the energy requirement of coral, therefore unless the coral can take on board new zooxanthellae (from the surrounding water) it will die.

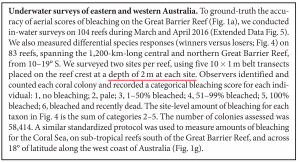

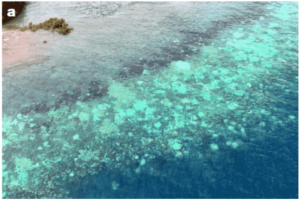

In this paper, it was concluded that very hot seawater associated with an El Nino event triggered a mass coral bleaching event. This event was documented by using aerial surveys of 1156 reefs which were each put in one of 5 categories of bleaching, ranging from severe (> 60% bleached) to no bleaching. This categorization was done by “visual assessment”, which then required ground-truthing to validate the accuracy. Ground-truthing was accomplished by “in-water surveys on 104 reefs” in which two sites per reef were selected, and the survey was made with divers on five 10 × 1 m belt transects placed on the reef crest at a depth of ~2 m at each site (See Figure 1). A very high correlation was found between the ground-truth surveys and the aerial assessment.

Possible caveat with this article

For example, Marshall and Baird (2000)[3] carried out a survey to discuss the bleaching event in March 1998. In contrast to Hughes et al (2017), Marshall and Baird’s dive transect survey was carried out at two depth ranges, 2-4 m and 5-8 m, because their survey was indeed conducted in areas mostly shallower than 10 m. Therefore, clearly Hughes et al’s (2017) methodology was not validated for any range between ~5 and ~40 meters, which is required for the GBR in general. Furthermore, the results of Frade et al. (2018)[4], which are commented at (WL9), were far more comprehensive than Hughes et al., (2017), and clearly show an overestimation on the Northern GBR by Hughes et al. (2017), although both these authors have not validated their results for deep-water reef in the Central and Southern GBR, where most of the GBR reef is located within.

Conclusions

Although this paper reports upon what was undoubtedly a major bleaching event, the methodology used puts in question the extent of the bleaching. In the future, surveys must also include the coral deeper than the very shallow surveys in this work, which were only at 2 m. Ideally, coral down to 40 m depth should also be surveyed.

References

- ↑ * [1] Hughes TP et al., (2017) Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals, Nature, 543: 373–377, doi:10.1038/nature21707

- ↑ * [2] Hopley, D., Smithers, S.G., and Parnell, K., (2007) The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef: development, diversity and change, Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511535543

- ↑ * [3] Marshall, P.A., and Baird, A.H., (2000) Bleaching of corals on the Great Barrier Reef: differential susceptibilities among taxa, Coral Reefs, 19: 155-163, doi:10.1007/s003380000086

- ↑ * [4] Frade, P.R., Bongaerts, P., Englebert, N., Rogers, A., Gonzalez-Rivero, M., Hoegh-Guldberg, O. (2018). Deep reefs of the Great Barrier Reef offer limited thermal refuge during mass coral bleaching. Nature Communicatiosns 9, article number: 3447, doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05741-0

Comments

In WL-Letters you have the freedom to respond to any caveat that may be inaccurate.

-- Andutta (talk) 00:13, 7 July 2022 (UTC)